Published 6 April 2020.

Join our STEM challenge and showcase your budding engineering skills and creativity

Share this story

We’ve been committed to supporting STEM initiatives across the UK through our partnership with Primary Engineer, to ensure we play our part in inspiring the next generation of engineers.

Around this time, we would have been attending fairs like the Big Bang, but as these events have not been able to go ahead, we are bringing a little bit of our Big Bang activity to you.

So we are setting you a challenge.

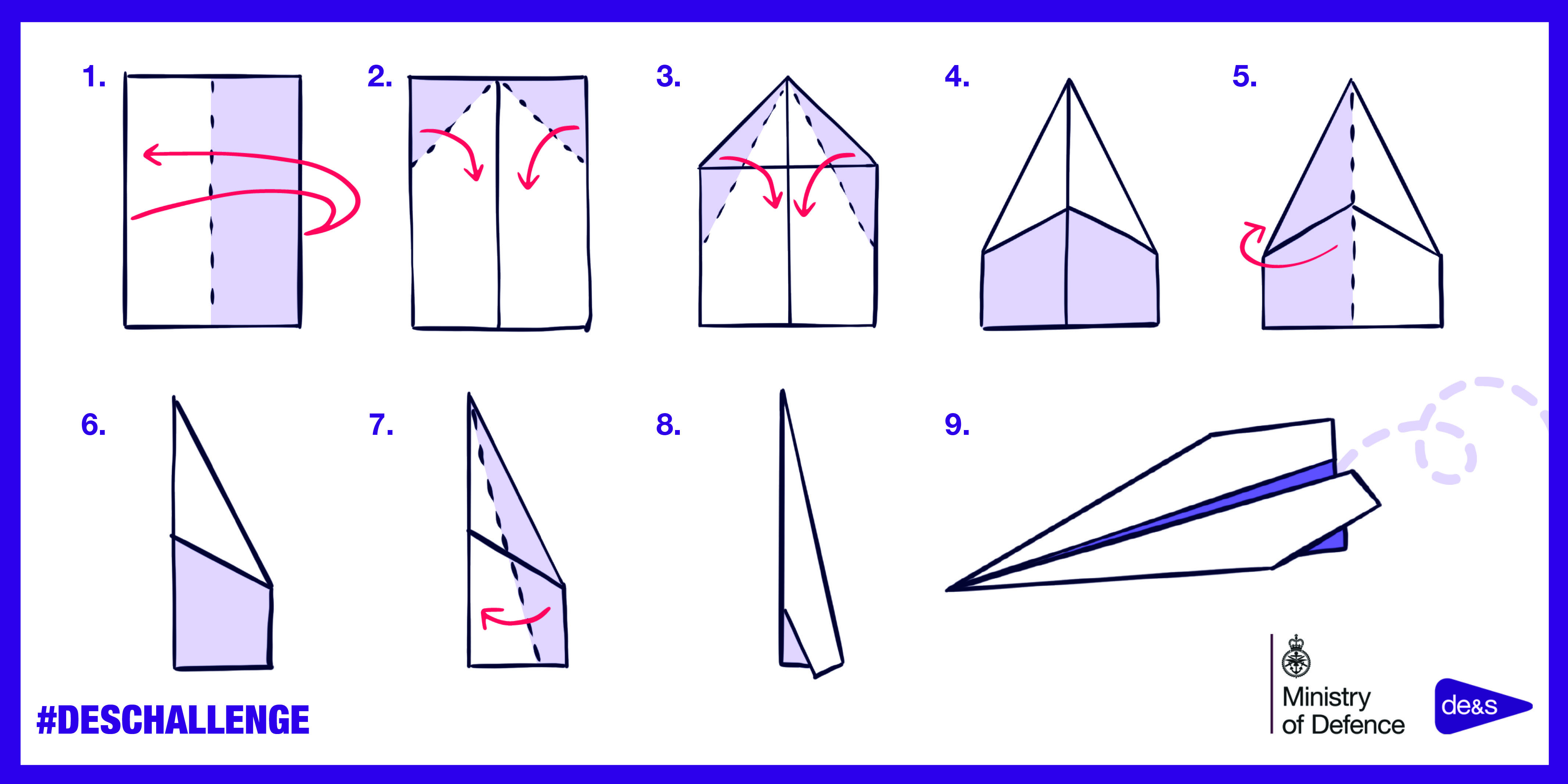

The paper plane challenge

We want you to build a paper plane out of any material you like and in any design, and film your efforts to show how far you can get your planes to fly.

Share them with us on our social media channels and measure the greatest distance that you’ve achieved. And then try to go one better – try adding extra winglets, a paperclip for ballast, or a Royal Air Force livery to make it stand out.

Try making planes of different sizes to compare how well they fly (do bigger planes fly further?) and try different materials to see if card is more effective than paper.

We’ll share all the entries that we get and ask our engineers to offer additional tips on how you can get your planes to fly further.

Be sure to use #DESChallenge when sharing your photos and videos and try to challenge your family and friends to see who can get their plane the furthest distance.

The aerodynamics of paper planes

Paper planes are subject to the same aerodynamic forces as a real plane – although the softness of paper makes them react a little differently to the ones used by the Royal Air Force.

However, this softness means that they can be easily adjusted, with subtle bends, curving and cuts to the wings able to make a big difference in how long they can stay in the air, and how stable they are.

The aerodynamic factors you must take into consideration are:

- Thrust – The force that gets the plane moving. In a standard plane this comes from its engines, but in a paper plane it is a matter of how hard you throw it – and finding the sweet spot is all-important. You need just enough to keep momentum, but not so much that the plane does a loop-the-loop and ends up behind you

- Drag – The amount of resistance that your plane creates in the air, which causes it to slow down and then lose height. This is the counter force to Thrust

- Lift – This is the force that is created by the wings and which keeps the plane in the air. The bigger the wings, the bigger the lift – but this comes at a cost of creating more drag. The wings on traditional planes are curved on the top and flat on the bottom to make the air move faster over the wing in order to create more lift – try giving this a go with you planes

- Gravity – Gravity is the force that all planes are fighting to stay in the air, and is the opposite to lift. The old saying “what does up must come down” means that you need to create a greater amount of lift than the effect that Gravity is having on your plane – Gravity is your biggest challenge in this task

How you can apply this knowledge in your future career

While the materials used may differ between a paper plane and the aircraft that we procure for the Royal Air Force and the Royal Navy, the principles are exactly the same.

Understanding how aerodynamics can be tweaked to make a plane more agile, to make it more stable, and to make it as efficient as possible is what engineers in the UK armed forces do on a daily basis – so getting a grip on these in paper form could help set you on a path to an engineering career in the future.

We look forward to seeing your creations and best efforts on social media.

In the meantime, you can find out more about the planes we procure for the RAF with our programme profiles – from the 1,200 mph F-35 Lightning, to the Typhoon which is capable of flying at 55,000 ft, and the enormous Atlas A400M cargo plane, which has a wing span of 42.4m.